Although I had taken a different interpretation, below, re Palmer's discussion, my view now is that technically a federalist unionist position, either way, either regarding the right of one or more states to secede, or the right of any federalist unionist government to split itself into two or more regional unionist states, whether all existing states were to agree to do so or not, by federal legislation, all such federal, or state, initiatives are inconsistent with the constitution's underlying source of authority in what it calls we the people.

If you look at Jefferson's late remarks in the blog below excerpt set out down below, you can see that he failed to see the problem "we the people" had created.

H welcomed with aplomb the ideas of either state secessions, and or the creation of regional blocs (presumably by federal decision either with or without component state and or territory agreement, by a territory, or by subsequent state composition.

Sunday, March 12, 2017

Sunday, March 26, 2017

RE THE CONSTITUTION FALLACIES

I haven't read enough Rawls to know that he commits the fallacy, but bet he does. Goes back to Locke, at least, really.

The Philadelphia convention, not we the people.

Going back to the states, not themselves created by we the people in the first instance, for ratification of the constitution, a conceptual no no.

Here, I am reading this into Palmer's account, or reading between the lines, perhaps.

It is hard to see how one could ever get, in the first instance, after the state of nature, to a ' we the people '. One could not even get to a conceptually flawed "original position", in anything other than a tiny city state, or better yet, a village. The city state, or a village, are, of course, not an original state of nature position.

See Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution, The Challenge, the section entitled "A Word on the Constitution of the United States", pb, p. 228.

Dual state federal citizenship creates another layer of conceptual inconsistency.

Does the federal we the people trump an individual state's, or even collective, states', we the people? I doubt whether Jefferson thought it would, if he even saw the problem at all. It seems certain that Lincoln did.

Friday, October 21, 2016

THE UNITED STATES CAN NEITHER CONSOLIDATE FURTHER NOR BREAK BACK INTO STATES OR SMALLER POLITICAL SUBDIVISIONS

Let me put your hearts at rest, if that is what you want to call it....

Founding Fathers' principles created a we the people political monster.

The way the Constitution was enacted, no state, or political subdivision thereof, could ever secede without the consent of all of the people of the United States first agreeing, not just state governments themselves in every single state, itself an impossibility, because mere state governments themselves are not the full, underlying, ' we the people ' envisioned by the framers.

We the people, all of us, would have to decide, if some of us, who assert they no longer wish to be part of us, want to separate from us.

In this sense, the United States is sort of a constitutionally beached whale, permanently.

Asian civilizations, of course, all know this, and have been feasting on our beached carcass, first the Japanese, since 1945.

The Japanese themselves even called this feasting process the ' hollowing out ' of the American economy.

It has continued heavily, especially since the Nixon Shock in 1971, and accelerating after 1980, by China.

What was left of the beached America carcass, after our politicians feebly brushed Japan away and invited China to the table instead, has been almost completely hollowed out by China.

Monday, October 19, 2020

ARTICLE III DK EXCERPT JUDICIAL POWER

"...The Supreme Court's power to test both state and federal laws against the text of our Constitution, and to strike down laws it finds in conflict with that text, was, I think, inherent in the text of the Constitution itself... " DK

"The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office." Constitution, Art. III.

Other sections of the Constitution deal with judicial courts of other federal branches.

The relations between these Articles is not made clear. Various different interpretations have been made. Bobbitt cites to Crosskey's interpretation. Constitutional Fate. It does not jive with the text of the Constitution. They are William Crosskey's erroneous inferences.

It is obvious that if Congress never acted, or later revoked authority, as it well might in years to come, there would be only a single federal supreme court.

The scope and extent of its powers and authority were not spelled out in the Constitution Art III, but the authority to overturn acts of Congress is very unlikely to have been a judicial power of the supreme court.

It is not at all clear that inferior federal courts, ordained and established, by Congress rather than by the supreme court, and terminable thereby, are accountable or jurisprudentially subordinate either administratively or decisionally to the supreme court rather than to Congress itself.

My suggestion to Democrats, supposing they gain control of Congress, is to summarily wind up, and disband, all inferior federal courts, lock, stock, and barrel, and slam the remaining supreme court with whatever it can then deal with, rather than engage in this ridiculous court packing further judicial inflation arms race.

State courts can succeed to lower federal case loads by whatever methods Congress deems appropriate. Lower federal courts are creatures of Congress, after all, not of the supreme court.

Think if this as my little suggestion for the problems DK outlines in this extended excerpt below from his current post:

"...The modern era of legislative jurisprudence, as one might call it, began after the Civil War, when conservative justices (and they were all conservative for much of the late 19th century) began using the 14th Amendment's guarantee of due process to outlaw state attempts to regulate their economy, including wages and hours legislation. Such rulings continued through the first four years of the New Deal, when they took down major New Deal laws, and they led to FDR's court packing plan, which failed dismally in Congress but convinced some moderate justices, led by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, to help affirm the Wagner Act and the Social Security Act to forestall a greater constitutional crisis.

"The broadening of the court's power entered a new phase, however, in Brown vs. Board of Education, when in 1954 the Warren Court ruled that school desegregation was an unconstitutional violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment. While the definitive work on that case, Richard Kluger's Simple Justice, showed pretty clearly that the authors of that amendment had not intended to outlaw segregated schools, the decision certainly reflected the broader purpose of that amendment, namely, to secure truly equal status for former slaves, which it defined specifically as citizens. In addition, Kluger showed that Chief Justice Warren, recognizing the gravity of the decision and the enormous impact that it would have, worked very hard, and successfully, to insure that the decision would be unanimous, even though the court at that time included several white southerners. The subsequent history of school desegregation in this country, however, shows how hard it is to impose such a change by judicial fiat. After decades of litigation, including 1970s decisions that approved school busing in some cases to promote integration, 69% of black children attend schools that are predominantly nonwhite. In parts of the Deep South, integration led almost immediately to the creation of a separate system of private "Christian" schools for white students, leaving the public schools almost completely segregated, and often underfunded as a result.

"During the next 15 years, the Warren Court issued a series of decisions that extended the reach of judicial power to try to transform various aspects of American life along more liberal lines. Several were based on the relatively new idea that all state legislation might be tested against the Bill of Rights, and at least one critical decision, on reapportionment, relied on relatively abstract ideas of justice. In the realm of criminal justice, Mapp vs. Ohio (1961) excluded evidence that had been seized without a warrant, Gideon vs. Wainwright guaranteed every defendant a lawyer, and Miranda vs. Arizona forced law enforcement agencies to inform defendants of their right to counsel and protection against self-incrimination. Reynolds vs. Sims and Baker v. Carr ordered states to apportion all their legislative districts according to population, rather than to favor rural districts against urban ones. Engel vs. Vitale (1962) outlawed organized prayer in public schools. New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) made it almost impossible for public figures to win libel suits in state court. While I certainly agree with the goals of all these decisions, every of them aroused considerable resentment against the courts because they bypassed or overruled the political process within states, and started the Republican assault upon the independence of the judiciary. These precedents had another impact. By continuing to test various specific state laws and practices against broad provisions of the U.S. Constitution, they encouraged a whole new style of litigation to which several generations of activist lawyers have devoted their lives. Rather than organize politically or run for office to try to achieve worthy goals, they look for ways to secure them in the federal courts, and thereby weaken our democratic processes.

"The expansion of judicial power took a new step forward in 1973, when the court handed down Roe v. Wade, making abortion legal all around the country. I personally regard that decision as tragic, even though I agree with its goal, because, when it happened, the political process was already attacking this issue with some success. The nation's two most populous states, New York and California, had already legalized abortion. That was beginning to trigger a nationwide political fight over the issue, but I think it's very likely that they would have maintained that right and that other states would have followed suit. Instead, Roe v. Wade made abortion advocates complacent, energized at least three generations of opponents to an extraordinary extent, and turned abortion into a critical national political issue that has distorted our politics ever since. Furthermore, new state laws and new federal court decisions have narrowed the right it decreed to such an extent that in much of the country it is almost impossible to secure a legal abortion, and a market for back-alley abortions has been created once again.

"By the time of Roe v. Wade, Richard Nixon, who in 1968 had campaigned explicitly against many of the Warren Court's decisions, had appointed four new members of the Supreme Court. By 1976, a conservative majority was using the Bill of Rights to invalidate major liberal legislation. In that year, Buckley v. Valeo held that the federal government could restrict a candidate's use of his own money in his election campaign, and two years later, in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, the court struck down a Massachusetts law designed to keep corporate money out of politics. These decisions laid the foundation for even more sweeping ones down the road.

"In 2003, in Lawrence v. Texas, the court struck down laws against sexual relations between gay people, and twelve years later, in Oberkfell v. Hodges, it established a right of gay marriage in every state. The former decision strikes me as a straightforward application of the equal protection clause, allowing consenting adults to choose their sexual partners. The latter, while just in my opinion, remains open to the same criticism as Roe v. Wade. By the time it was handed down the political processes in many states had already legalized gay marriage and that would have continued. As it is, gay marriage, as we shall see, is now under attack from another Constitutional angle.

"The appointment of two members of a new generation of conservative justices, John Roberts and Samuel Alito, by George W. Bush--who was forced by his own party to abandon what would probably have been a more moderate appointment--allowed the court to move three critical areas of policy in a conservative direction, each time by a 5-4 vote. In District of Columbia v. Heller, the court overruled more than two centuries of precedent and almost completely eliminated a state's right to regulate the possession of firearms. Citizens United v. FEC (2010) essentially ended any restrictions on corporate spending on election campaigns, overturning a century of federal laws. And in Shelby County v. Holder(2013), the same 5-4 majority invalidated the key preclearance provision of the Voting Rights Act--perhaps the most obvious judicial usurpation of legislative power in the history of the Republic. The 15th Amendment explicitly gave Congress the right to enforce itself by appropriate legislation, and the Voting Rights Act had repeatedly been renewed by large Congressional majorities. The court majority threw out the provision simply because they, in contrast to Congress, did not regard as fair or necessary any longer. Numerous states have passed legislation attempting to reduce voting in response.

"No one, really, should be surprised that both political powers have tried to bend the enormous power of the Supreme Court as it has evolved since the Second World War to their own purposes. Democrats are especially frustrated at this moment, first, because luck as well as electoral politics have given Republicans so many more court appointments than Democrats over the last 50 years, and secondly, because the Republican Senate majority shamelessly used its power four years ago to deny President Obama an appointment that rightfully belonged to him, and having made sure then that Justice Scalia would be replaced by another conservative, they are making sure now that Justice Ginsburg will be, as well. The situation we are in, however--in which the appointment and confirmation of federal justices may well have become the single most important thing that the President and the Senate do--reflects a long deterioration of American democracy, which has taken so many decisions out of the voters' hands.

"Eleven years ago, the political scientist James MacGregor Burns--then 92 years old--published a remarkable history of the politics of the Supreme Court, Packing the Court, which I reviewed at the time. Burns as a college student had lived through the battle between the Court and the New Deal, and that had left him with a firm belief that the Court should not be allowed to invalidate acts of Congress. That book railed against the enormous role of the Court in our political life, and looked forward to the day when a President might defy its attempt to invalidate a law. That, it seems to me, might be a more effective step for a new President Biden to take than a new attempt to add justices to the Court, if the Roberts Court, as seems fairly likely, does confirm the argument that Roberts himself made when the ACA first came before it, and tries to invalidate the ACA on the grounds that without the tax that went along with the individual mandate, it is now unconstitutional." DK

Friday, May 4, 2018

RANDALL COLLINS GUN CULTS

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 14, 2018

GUN CULTS

Thursday, May 28, 2020

THE 1619 PROJECT GOT SOME THINGS RIGHT Did a Fear of Slave Revolts Drive American Independence?

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/04/opinion/did-a-fear-of-slave-revolts-drive-american-independence.html

What a bunch of utter reeking bullshit. The colonists themselves had taken into ports, and trafficked in, slaves from slave traders, and from pirate prizes, whether the King had allowed them to or not.

Yellow Creek Massacre, Wikipedia, is also fun reading, re indians; 'America's "Heart of Darkness"', Parkinson.

Ethiopian Regiment, Wikipedia; Battle of Kemp's Landing; Battle of Great Bridge; Colonel Tye; Black Pioneers; African Americans in the Revolutionary War; Franco-American Alliance

Take a look at Allison, Before 1776. The Teaching Company. The fricking colonists had been supposed to keep their sorry asses within colonial areas. They tended never to do that. It wasn't, of course, a guarantee of their safety, but what was the alternative.

Jefferson's rough draft:

INTRODUCTION

THE WRITINGS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON, EDITED BY H. A. WASHINGTON (NEW YORK: JOHN C. RIKER, 1853).

A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled

EDITOR: THE TWO FINAL PARAGRAPHS, IN THEIR ORIGINAL AND AMENDED FORMS, WERE PLACED NEXT TO EACH OTHER IN H. A. WASHINGTON’S EDITION: THE ORIGINAL DRAFT APPEARED IN A LEFT HAND COLUMN, AND THE AMENDED AND FINAL VERSION WERE PLACED IN A RIGHT HAND COLUMN.

Sunday, March 12, 2017

JEFFERSON AND SECESSION BLOG QUOTATIONS

Thomas Di Lorenzo:

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

–Letter from Thomas Jefferson to William Stephens Smith, Nov 13, 1787Thomas Jefferson, the author of America’s July 4, 1776 Declaration of Secession from the British empire, was a lifelong advocate of both the voluntary union of the free, independent, and sovereign states, and of the right of secession. “If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form,” he said in his first inaugural address in 1801, “let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left to combat it.”

In a January 29, 1804 letter to Dr. Joseph priestly, who had ask Jefferson his opinion of the New England secession movement that was gaining momentum, he wrote: “Whether we remain in one confederacy, or form into Atlantic and Mississippi confederacies, believe not very important to the happiness of either part. Those of the western confederacy will be as much our children & descendants as those of the eastern . . . and did I now foresee a separation at some future day,, yet should feel the duty & the desire to promote the western interests as zealously as the eastern, doing all the good for both portions of our future family . . .” Jefferson offered the same opinion to John C. Breckenridge on August 12 1803 when New Englanders were threatening secession after the Louisiana purchase. If there were a “separation,” he wrote, “God bless them both & keep them in the union if it be for their good, but separate them, if it be better.”

Documents Relating To ...Best Price: $29.90Buy New $29.96

Documents Relating To ...Best Price: $29.90Buy New $29.96Everyone understood that the union of the states was voluntary and that, as Virginia, Rhode Island, and New York stated in their constitutional ratification documents, each state had a right to withdraw from the union at some future date if that union became harmful to its interests. So when New Englanders began plotting secession barely twenty years after the end of the American Revolution, their leader, Massachusetts Senator Timothy Pickering (who was also George Washington’s secretary of war and secretary of state) stated that “the principles of our Revolution point to the remedy – a separation. That this can be accomplished without spilling one drop of blood, I have little doubt” (In Henry Adams, editor, Documents Relating to New-England Federalism, 1800-1815, p. 338). The New England plot to secede from the union culminated in the Hartford Secession Convention of 1814, where they ultimately decided to remain in the union and to try to dominate it politically instead. (They of course succeeded beyond their wildest dreams, beginning in April of 1865 up to the present day).

John Quincy Adams, the quintessential New England Yankee, echoed these Jeffersonian sentiments in an 1839 speech in which he said that if different states or groups of states came into irrepressible conflict, then that “will be the time for reverting to the precedents which occurred at the formation and adoption of the Constitution, to form again a more perfect union by dissolving that which could no longer bind, and to leave the separated parts to

Jubilee of the Constit...Best Price: $10.50 be reunited by the law of political gravitation . . .” (John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution, 1939, pp. 66-69).

Jubilee of the Constit...Best Price: $10.50 be reunited by the law of political gravitation . . .” (John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution, 1939, pp. 66-69).There is a long history of American newspapers endorsing the Jeffersonian secessionist tradition. The following are just a few examples.

The Bangor, Maine Daily Union once editorialized that the union of Maine with the other states “rests and depends for its continuance on the free consent and will of the sovereign people of each. When that consent and will is withdrawn on either part, their Union is gone, and no power exterior to the withdrawing [state] can ever restore it.” Moreover, a state can never be a true equal member of the American union if forced into it by military aggression, the Maine editorialists wrote.

“A war . . . is a thousand times worse evil than the loss of a State, or a dozen States” the Indianapolis Daily Journal once wrote. “The very freedom claimed by every individual citizen, precludes the idea of compulsory association, as individuals, as communities, or as States,” wrote the Kenosha, Wisconsin Democrat. “The very germ of liberty is the right of forming our own governments, enacting our own laws, and choosing or own political associates . . . . The right of secession inheres to the people of every sovereign state.”

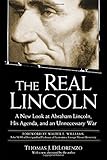

The Real Lincoln: A Ne...Best Price: $3.08Buy New $7.62Using violence to force any state to remain in the union, once said the New York Journal of Commerce, would “change our government from a voluntary one, in which the people are sovereigns, to a despotism” where one part of the people are “slaves.” The Washington (D.C.) Constitution concurred, calling a coerced union held together at gunpoint (like the Soviet Union, for instance) “the extreme of wickedness and the acme of folly.”

The Real Lincoln: A Ne...Best Price: $3.08Buy New $7.62Using violence to force any state to remain in the union, once said the New York Journal of Commerce, would “change our government from a voluntary one, in which the people are sovereigns, to a despotism” where one part of the people are “slaves.” The Washington (D.C.) Constitution concurred, calling a coerced union held together at gunpoint (like the Soviet Union, for instance) “the extreme of wickedness and the acme of folly.”“The great principle embodied by Jefferson in the Declaration of American Independence, that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,” the New York Daily Tribune once wrote, “is sound and just,” so that if any state wanted to secede peacefully from the union, it has “a clear moral right to do so.”

A union maintained by military force, Soviet style, would be “mad and Quixotic” as well as “tyrannical and unjust” and “worse than a mockery,” editorialized the Trenton (N.J.) True American. Echoing Jefferson’s letter to John C. Breckenridge, the Cincinnati Daily Commercial once editorialized that “there is room for several flourishing nations on this continent; and the sun will shine brightly and the rivers run as clear” if one or more states were to peacefully secede.

Hamilton's Curse: How ...Best Price: $8.19Buy New $41.98

Hamilton's Curse: How ...Best Price: $8.19Buy New $41.98All of these Northern state editorials were published in the first three months of 1861 and are published in Howard Cecil Perkins, editor, Northern Editorials on Secession (Gloucester, Mass.: 1964). They illustrate how the truths penned by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence – that the states were considered to be free, independent, and sovereign in the same sense that England and Francewere; that the union was voluntary; that using invasion, bloodshed, and mass murder to force a state into the union would be an abomination and a universal moral outrage; and that a free society is required to revere freedom of association – were still alive and well until April of 1865 when the Lincoln regime invented and adopted the novel new theory that: 1) the states were never sovereign; 2) the union was not voluntary; and 3) the federal government had the “right” to prove that propositions 1 and 2 are right by means murdering hundreds of thousands of fellow citizens by waging total war on the entire civilian population of the Southern states, bombing and burning its cities and towns into a smoldering ruin, and calling it all “the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

Happy Fourth of July!

No comments:

Post a Comment