| Entry | Pageviews |

|---|---|

United States

|

21

|

Portugal

|

13

|

South Korea

|

8

|

Ukraine

|

4

|

Canada

|

2

|

Russia

|

1

|

South Africa

|

1

|

BOOMERBUSTER

OLD CELLO

Saturday, February 29, 2020

WE FORCED TURKS ON OCCUPIED GERMANY 1961 BIG FUCKING GASTARBEITER BLUNDER

RATHER LIKE LINCOLN FREEING THE NEGROES WITHOUT TRANSPORTATION

Wikipedia:

Wikipedia:

The first Gastarbeiter were recruited from European nations. However Turkey pressured the Federal Republic to allow its citizens to become guest workers.[1] Theodor Blank, Secretary of State for Employment, was opposed to such agreements. He held the opinion that the cultural gap between Germany and Turkey would be too large and also held the opinion that Germany needed no more labourers because there were enough unemployed people living in the poorer regions of Germany who could fill these vacancies. The United States, however, put some political pressure on Germany, wanting to stabilize and create goodwill from a potential ally. The German Department of Foreign Affairs carried on the negotiations after this, and in 1961 an agreement was reached.[6][6]

EU BOUND THEY LOOK REAL PEACE LOVING

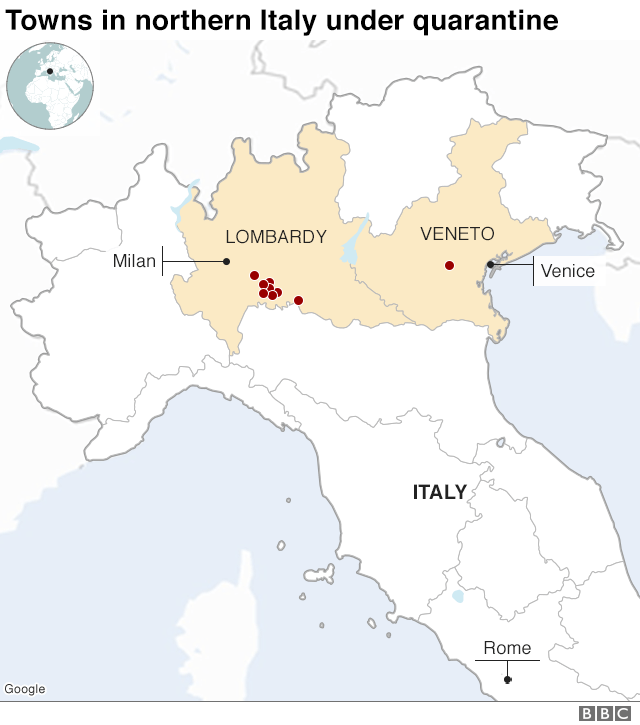

NO DOUBT THOUSANDS ARE ALSO MIGRANTS ESCAPING IRAN CORONAVIRUS PETRI DISH CONDITIONS AND ARE CARRYING IT NOW TO EUROPE IN LARGE NUMBERS

IF THE GREEKS SHOOT A BUNCH OF THEM THEY WILL STOP TRYING TO LEAVE THE MIDDLE EAST, AFRICA, AND ASIA.

THAT IS MY SUGGESTION.

ALSO, ATTACK COUNTRIES, LIKE TURKEY, WHICH LET THEM DEPART.

IF YOU LET THEM IN, YOU BITCH, YOU ARE STUCK WITH THEM.

Friday, February 28, 2020

TIME FOR THE EU AND GREECE BALKAN STATES TO FIRE ON TURKEY

Syria war: Turkey lets refugees exit towards Europe

Turkey breaks a deal.

Thursday, February 27, 2020

DAVID REICH ALLEN LECTURE MORE AND MORE CONQUEST EVIDENCE PILING UP

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d78fERhnrNc

He talks here about a population roaring into the Iberian peninsula, conquering those there, killing enslaving and or eating the males, and then porking, for generations, all the conquered women who lived there before.

Great stuff!

This pattern recurs over and over again in his ancient DNA accounts, all over Eurasia.

He calls this mixing, and describes it as a good thing.

What is he smoking?

He never talks about the conquerors' own womenfolk, what happened to them, killed and or eaten before the expedition, left behind to fend for themselves, brought along but never mated with again, whatever.

One implication is that the conqurors did not abuse these women as much as they did the new victims.

The conquerors oppressed new female victims, but then what had they done to the old ones, given them awards for loyal service?

They drop from sight almost as peacefully as his account of how the Neanderthals went down to a higher more advanced power the modern humans as if it happened almost overnight, a Lockean tabula rasa wiped clean and overwritten.

JFK RFK KENNEDY MONROE LAWFORD GIANCANA HOOVER HOFFA

The Mafia killed the Kennedys, but the Kennedys, not the Mafia, killed Marilyn.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXfFC0Dv1tM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXfFC0Dv1tM

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

RE ENERGYFLOW REFERENCE TO THIS BLOG READ THE COMMENTS GREAT DRIVEL

https://econimica.blogspot.com/2020/01/what-does-lowest-population-growth-in_31.html

IRAN IS JUST GOING TO GUT IT OUT!

Now would be a great time not to try to open Iran's market or society to the degenerate West!

BRITISH CONTINUED COOLIE SLAVE LABOR UNTIL 1917 FAKED AMERICAN ABOLITIONISTS OUT ON ENDING SLAVERY IN 1833

After the British Empire ended slavery in 1833, plantation owners returned to indentured servitude for labor, with most servants coming from India,[10] until the British government prohibited the practice in 1917.

INDENTURED SERVITUDE I DIDN'T KNOW UP TO TWO THIRDS OF WHITES OR INTO 20TH C

Between the 1630s and the American Revolution, one-half to two-thirds of white immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies arrived under indentures

Indentured servitude continued in North America into the early 20th century

WIKIPEDIA

Indentured servitude continued in North America into the early 20th century

WIKIPEDIA

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

BRITISH YIMBYS NEED TO MARKET HIGH RISES IN WEST AFRICA SAY LIBERIA OR BRAZIL (MY WEST AFRICA)

Don't try it on in Cornwall.

WHY LET MARKETS DETERMINE HUMAN CULTURE? SLAVE MARKETS ARE PERFECTLY RATIONAL

Slavery in the Byzantine Empire

Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

Slave market

Wikipedia

Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

Slave market

Wikipedia

It did not. By the end of West Rome, 30–40% of Italians were slaves and 10–15% in the whole empire. Many had been freed and turned into serfs for farming reasons though. Like in later feudal medieval times.

Byzantium kept the big slave market by Crimea and Constantinople alive, together and in competition with Khazars, Venetians, Varangians and others, and enslaved Slavs and others. Until the Ottomans took over and continued the practice of taking household and sexual slaves from the Balkans to the great city. And the Crimean Tatarian Khanate took over Crimea.

Iberia had thrown out the Muslims by then, and instead used the Arab slave trade to start the Transatlantic slave trade to New India, and the Parthian slave trade from Old India as well.

PAGEVIEW RIGHT NOW

| Entry | Pageviews |

|---|---|

Dec 15, 2017

|

1

|

This old cello I take to be a close variation on the form B piccolo, the same barrel baroque, but relatively low, profile, slightly shorter, more rounded and appealing Cs, as well as beautiful full size, correct, form B f holes. They look great on this small cello.

OLD POST LATER DEDICATED TO GRETA THUNBERG

Sunday, March 20, 2011

RE MERCILESS GLOBAL MARKETS THOMAS FRIEDMAN PICKING WINNERS THE WAR WITH NO NAME BEHIND THE COLD WAR HAS NOW BEEN LOST

Some globalist pundits are now talking about what the future holds for their kids, backpedaling fiercely against the global economic and military tsunami they extolled the virtues of for decades, now barreling down on them, and their children, and their childrens' children, and us, and ours.

I am going to spell out a few things that they should have been thinking about for a long long time, since the mid 60s at least.

Has it been wise, if you were worried about the world for your kids, to put off your domestic labor issues, to put government against labor as a class in favor of management, to favor foreign over domestically produced goods, to allow your corporations to offshore jobs, and then factories, and then major investments;

has it been wise to think mainly only in relatively short term profitability, as a criterion, for anything, anything, if you were worried, really worried, about your kids, or their kids?

Let's talk briefly about the issue of labor and unions.

Offshoring capacity, and buying foreign goods and services, not only puts your own domestic work force out of work permanently, but also puts the labor force and capital investments of your new global economy at the political, ideological, economic, ethnic, civilizational, and military command of foreign governments,

which can change, sometimes quite drastically, sometimes to a political stance contrary to your wishes, sometimes almost overnight,

always however, it seems, transforming fairly quickly, say in 20 years nowadays, the lapse of one generation,

from a cheap source of labor or materials into a more expensive, and adversarial, competitor.

That has been the pattern over and over again now for at least 50 years.

How do you 'bust', or for that matter, defend, a foreign labor force, when a foreign regime supports other pressing agendas; like taking over world domination; or dominating its neighbors where you also may have large investments; or dominating your other markets; or dominating your domestic market; or controlling, or taking over your domestic political system, against your own narrow corporate interests, just for a few little examples?

That all kind of starts to sound a great deal worse than would have been simply dealing with domestic management and labor issues in the first place, and trying to keep as much production and consumption as possible domestic, and to build a stronger well integrated domestic economy.

Many other implications beside labor or unions flowed from foreign investment, trade concessions, and offshored production. The process really started before WW II, and accelerated with the Marshall Plan, and then especially with Cold War trade and market concessions.

Most people (I mean mainly intellectuals now; almost no one reads Fukuyama in reality) do not know it, they read things like The End Of History And The Last Man, and follow people like Fukuyama, and actually believe that the US, and its ideology 'won' what it calls the Cold War.

Pundits like Thomas Friedman actually buy this 'Whig Interpretation' (see Butterfield's sense of the term);

and Prestowitz follows Fukuyama and Friedman in Rogue Nation, buying Friedman's foolish pronouncements, and giving a credibility to Fukuyama's bizarre idealogical positions.

Contrary to their rather puerile views, my view is that The War With No Name that has quietly been waged 'by other means' as Clausewitz so aptly had put it ("War is not merely a political act, but also a political instrument, a continuation of political relations, a carrying out of the same by other means") simultaneously with the Cold War, call it 'The War For Picking Winners In The World Of The Future', has now been lost.

More on these themes shortly.

Terms search Krugman Thomas Friedman David Brooks Milton Friedman Fukuyama Chalmers Johnson Prestowitz Eckes Fallows Van Wolferen Ohmae George Friedman Meredith LeBard Maverick Executive Mise en scene cartoon Macaire

Monday, February 24, 2020

JUNGLE DIALOGUE 2095

Where are we?

Not far from the coast.

Pretty overgrown.

Yeah.

Any humans?

Only cannibals.

Any idea what this place is?

Used to be called Hollywood.

Not far from the coast.

Pretty overgrown.

Yeah.

Any humans?

Only cannibals.

Any idea what this place is?

Used to be called Hollywood.

RE KEYNES AND US WARREN MARKETS AND US

A note re Unknown's, comment "...I believe Sen. Elizabeth Warren understands this better than any other Democratic candidate. She knows that unregulated capitalism is just greed...":

"...Friends and colleagues of Warren's from her high school days to the early part of her academic career in the 1980s have characterized her as a "die-hard conservative" with a belief in laissez-faire economics and "surprisingly anti-consumer views". Gary L. Francione, who had been a colleague of hers at the University of Pennsylvania, recalled in 2019 that when he heard her speak at the time she was becoming politically prominent, he "almost fell off [his] chair... She’s definitely changed".[29] Warren was registered as a Republican from 1991 to 1996.[1] She voted Republican for many years. "I was a Republican because I thought that those were the people who best supported markets", she has said.[7] But she has also said that in the six presidential elections before 1996 she voted for the Republican nominee only once, in 1976, for Gerald Ford.[29] Warren has said that she began to vote Democratic in 1995 because she no longer believed that the Republicans were the party who best supported markets,.." Wikipedia

SANDERS' HONEYMOON BABY

(The couple did travel to the Soviet Union after their wedding,...

May 3, 2019 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

“Let’s take the strengths of both systems,” he said upon completing the trip. “Let’s learn from each other.”

The Soviet sojourn has long been an extraordinary, if little understood, chapter in Sanders lore. He has for years used it to help explain his views about foreign policy, citing it as recently as last month.

The trip garnered brief mention in the 2016 presidential campaign, but earlier this year, a video from a Vermont community television station was posted online that showed a few minutes of Sanders’s unlikely celebration with the Soviets. Right-leaning websites suggested Sanders was cozying up to communists, underscoring how the trip might be used against the senator if he becomes the Democratic nominee.

Until now, however, relatively few details about the trip have emerged, and most accounts have relied heavily on Sanders’s recollection. An examination by The Washington Post of the trip — based on interviews with five people who accompanied Sanders, as well as audio and video of it — provides a fresh look at this formative time for Sanders, foreshadowing much of what animates his presidential bid.

As he campaigns for president a second time, Sanders, an Independent who is running in the Democratic primaries, takes credit for moving the party to the left, and he now finds himself competing with candidates who advocate for the kind of activist government positions Sanders touted during his Soviet trip, such as government-sponsored health care for all.

As he stood on Soviet soil, Sanders, then 46 years old, criticized the cost of housing and health care in the United States, while lauding the lower prices — but not the quality — of that available in the Soviet Union. Then, at a banquet attended by about 100 people, Sanders blasted the way the United States had intervened in other countries, stunning one of those who had accompanied him.

“I got really upset and walked out,” said David F. Kelley, who had helped arrange the trip and was the only Republican in Sanders’s entourage. “When you are a critic of your country, you can say anything you want on home soil. At that point, the Cold War wasn’t over, the arms race wasn’t over, and I just wasn’t comfortable with it.”

Sanders declined to be interviewed for this report. Jeff Weaver, his senior adviser, said the trip fits into Sanders’s effort to form partnerships between people who may seem at odds with each other.

“Just like his politics in the U.S. are animated by bringing ordinary people together,” Weaver said, the trip to the Soviet Union “was an example of that, if you can get people from everyday walks of life together, you can break through some of the animosity that exists on a governmental level.”

Sanders has often emphasized the difference between his views as a democratic socialist and communist dogma, noting that he supports democratic elections and business enterprises that were inimical to the Soviet system. Sanders, who in 1988 had been mayor of Burlington for seven years, took the trip at a time when he was trying to put himself on the national stage. He wrote that Burlington, a city of about 40,000, had a foreign policy because, “I saw no magic line separating local, state, national and international issues . . . How could issues of war and peace not be a local issue?”

He was already known as a firebrand on foreign affairs, finding much to like in socialist and communist countries.

Sanders had visited Nicaragua in 1985 and hailed the revolution led by Daniel Ortega, which President Ronald Reagan opposed. “I was impressed,” Sanders said then of Ortega, while allowing that “I will be attacked by every editorial writer for being a dumb dope.” At the same time, Sanders voiced admiration for the Cuban revolution led by Fidel Castro, whom Reagan and many others in both parties routinely denounced.

Sanders, in turn, said Americans dismissed socialist and communist regimes because they didn’t understand the poverty faced by many in Third World countries. “The American people, many of us, are intellectually lazy,” Sanders said in a 1985 interview with a Burlington television station.

The trip to the Soviet Union was, at that time, Sanders’s most significant foreign venture. U.S. relations with the Soviet Union were in the midst of transformation. Just before Sanders departed, Reagan traveled to Moscow for a summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who was pushing for openness and reform. As a result, Sanders muted his criticism of Reagan, praising the summit as “a major step forward for humanity. . . . What we are doing is actually the same thing at a lower level.”

The timing of Sanders’s trip drew much notice. He got married before a crowd of hundreds in Burlington. “On the next day we began a quiet, romantic honeymoon,” Sanders wrote in his book “Outsider in the White House,” jocularly describing the journey with his bride, Jane, and about 10 others.

“It cost him some political capital when you are self-identified as a socialist and you go to the Soviet Union,” said Terrill G. Bouricius, who accompanied Sanders as a Burlington City Council member. “We knew there would be some negative effects of that, but we thought pushing peaceful coexistence was important.”

The trip had its genesis a year earlier, when Kelley helped arrange for a Soviet choir of about 30 girls to visit Burlington. After staying with local families and visiting schools, the choir performed for about 500 residents, and Sanders asked to take the stage. At one point, according to Kelley, Sanders pointed to the choir and said, “This is the enemy?”

The main purpose for the trip to the U.S.S.R. was to establish Burlington’s “sister city” in the Soviet Union. Kelley said he initially proposed that Burlington partner with Kaunas, Lithuania, but he said Sanders, who is Jewish, rejected that idea because thousands of Jews had been killed there by the Nazis in 1941.

PREHISTORIC DNA FOIBLES INDIA LOVES THE MIDDLE EAST

The prehistoric off white West Eurasians (Aryans, or Yamnaya, or whatever) stormed into India, slaughtered or enslaved all the brown midget, ANI and ASI males, and porked all the ANI and ASI midget women, for many generations. Not 80 year cycles.

Apparently, their descendants, West Eurasian offspring, became what later became known as the Brahmin Caste in India.

Reich analogizes it to the American south, white on negro, and to Spanish America, ditto.

I see his point. Great point!

Apparently, their descendants, West Eurasian offspring, became what later became known as the Brahmin Caste in India.

Reich analogizes it to the American south, white on negro, and to Spanish America, ditto.

I see his point. Great point!

See, David Reich, Ch 6.

ROOSKIE PORNTELS IMAGINE WHAT THEY HAVE ON YOU "I WAS IN A RELATIONSHIP"!

Monday, February 24, 2020

THE WEINSTEIN VERDICT WILL HAVE A VERY CHILLING EFFECT ON PROSTITUTION

Why would rich JOHNS now risk life in prison by paying a prostitute a few thousand dollars?

She can claim it was a relationship!

She can get paid by the hour, complain if the relationship stops, move on if necessary to blackmail and or extortion, and if that fails go to the state attorney as a rape victim!

This makes extortion and blackmail by organized crime a whole lot easier!

She can claim it was a relationship!

She can get paid by the hour, complain if the relationship stops, move on if necessary to blackmail and or extortion, and if that fails go to the state attorney as a rape victim!

This makes extortion and blackmail by organized crime a whole lot easier!

THE WEINSTEIN VERDICT WILL HAVE A VERY CHILLING EFFECT ON PROSTITUTION

Why would rich JOHNS now risk life in prison by paying a prostitute a few thousand dollars?

She can claim it was a relationship!

She can get paid by the hour, complain if the relationship stops, move on if necessary to blackmail and or extortion, and if that fails go to the state attorney as a rape victim!

This makes extortion and blackmail by organized crime a whole lot easier!

She can claim it was a relationship!

She can get paid by the hour, complain if the relationship stops, move on if necessary to blackmail and or extortion, and if that fails go to the state attorney as a rape victim!

This makes extortion and blackmail by organized crime a whole lot easier!

JESSICA MANN GIVE ME A BREAK UNCHARGED PROSTITUTE

The jury apparently bought her as a victim.

She confessed to basically ongoing prostitution, on the stand, under oath, in open court.

More dumb jury.

She confessed to basically ongoing prostitution, on the stand, under oath, in open court.

More dumb jury.

BUYING WESTERN STRATEGIC ASSETS OR AVAILABLE FOR FREE OR STRAIGHT ESPIONAGE

DON'T YOU THINK IT'S A LITTLE LATE, SIX DECADES LATE, TO BE WORRYING ABOUT SHIT LIKE THIS?

GAME OVER, SMELL THE COFFEE

https://www.npr.org/2020/02/14/806128410/harvard-professors-arrest-raises-questions-about-scientific-openness

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/harvard-professor-charged-with-hiding-china-ties

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-crime/us-charges-harvard-professor-with-lying-about-role-in-chinese-research-idUSKBN1ZR23V

Boston has always been the slut of all sumps.

TOO LATE TO BLOCK THE SUMP

Not just Harvard, the now exposed upper tip of the putrid festering sump.

GAME OVER, SMELL THE COFFEE

https://www.npr.org/2020/02/14/806128410/harvard-professors-arrest-raises-questions-about-scientific-openness

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/harvard-professor-charged-with-hiding-china-ties

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-crime/us-charges-harvard-professor-with-lying-about-role-in-chinese-research-idUSKBN1ZR23V

Boston has always been the slut of all sumps.

TOO LATE TO BLOCK THE SUMP

Not just Harvard, the now exposed upper tip of the putrid festering sump.

STALIN WEIMAR HITLER

Stalin kept supporting the German communists against both Weimar and then the against the Nazis right up until the end. Stalin was unconcerned whether Hitler's Party took power if Weimar fell. See eg Childers, A History of Hitler's Empire, The Teaching Company.

Why shouldn't Putin be doing something even more nefarious now, supporting Trump and supporting Sanders simultaneously?

The fact that Sanders has loudly snubbed Putin should not mislead anyone into doubting that Sanders is an ad hoc Soviet asset, whether he claims to like it, or Putin, or not.

That in fact is what he Putin is doing.

Sunday, February 23, 2020

THE HOLOCAUST MIGHT JUST AS EASILY HAVE BEEN A FRENCH AS A GERMAN AFFAIR GIVEN THE DREYFUS AFFAIR ATMOSPHERE

The French would just as readily have exterminated their Jews, and almost did during the Dreyfus Affair, as the Germans eventually did.

Ditto the Austrians, the Dutch, the Belgians, the British, the Italians, the Spanish, etc.

Maybe that is why the Dutch, especially, have apologized recently.

Faux bad conscience, not just brute fear of immediate death if they failed to do the Nazis' bidding. You tell me the truth.

Don't kid yourself.

Maybe that is another reason the Allies waited so long for the Crusade in Europe, let the Germans kill off the Russians, and vice versa, and let the Germans and Russians kill off the Jews, a goal everyone apparently wanted.

Ditto the Austrians, the Dutch, the Belgians, the British, the Italians, the Spanish, etc.

Maybe that is why the Dutch, especially, have apologized recently.

Faux bad conscience, not just brute fear of immediate death if they failed to do the Nazis' bidding. You tell me the truth.

Don't kid yourself.

Maybe that is another reason the Allies waited so long for the Crusade in Europe, let the Germans kill off the Russians, and vice versa, and let the Germans and Russians kill off the Jews, a goal everyone apparently wanted.

IPHONE SECURITY OXYMORON

"If he wants to call me, tell him to use a phone card and a pay phone not his. He is always recorded, by everyone, trust me. Russians, Ukrainians, Brits, CIA, Chinese, you name it."

LINCOLN'S ELECTION LED TO SECESSION WHAT IF SANDERS'?

"...The supposed unelectability of Bernie Sanders, the Democratic front runner, is not supported by the data at all.... The survival of democracy here and elsewhere is once again the key issue of our crisis, just as in 1861 and 1932...." DK

If Sanders is elected, democracy does not survive.

If Sanders is defeated, democracy does not survive.

Morton's Fork

Another example of Morton's fork is a swim test for witchcraft that was performed in the Early Modern period. The suspected witch was tied up and thrown in the water. If they floated, that was considered to be proof of witchery. If the suspect sank and drowned, they were deemed innocent. Either way, the outcome was the same; the test subject died.

LAISSEZ FAIRE CAPITALISM VS PROTECTIONISM US HISTORY

See Protectionism in the United States, wikipedia

THOMAS L FRIEDMAN BROTHER FLATTER BITES THE FLAT DUST IN CA

'Mad' Mike Hughes dies after crash-landing homemade rocket

Hughes was well-known for his belief that the Earth was flat. He hoped to prove his theory by going to space.

Saturday, February 22, 2020

DID LINCOLN WANT FREED NEGROES TO VOTE OR TO BE TRANSPORTED? BIG DIFFERENCE!

If the Deomcrats take power, they could then enfranchise all Africans as sudden voters, 1.2 billion of them, who would then vote Democrat!

If white women had been voting in 1860, they would have freed all those negro slaves right away!

They weren't afraid of them! They loved them!

They just weren't given the vote!

If white women had been voting in 1860, they would have freed all those negro slaves right away!

They weren't afraid of them! They loved them!

They just weren't given the vote!

WEINSTEIN JURY I HAVE A SHOT DEADLOCKED NO PARTIAL VERDICT NO SPLITS BABY!

You see, I may have guessed right, but dangerous to predict.

Nevertheless, I vote mistrial at this point.

Wednesday, October 25, 2017

re I LOVE PHILOSOPHY 2013 POST SOMEONE SAW

"Sunday, November 7, 2010

MISE EN SCENE BUS STOP MAVERICK EXECUTIVE MARILYN FREE TRADE HUMAN RIGHTS HOLD UP AND UGLY PHILOSOPHERS

We show the Maverick in his cowboy get up, dressed for the rodeo, with six shooters strapped on, ten gallon hat; Uncle Sam goatee. He has dismounted an older mare. He is wearing a prominent Sheriff's Badge with pointy ends.

He has stopped a stage coach (the large old kind, seen in Westerns; 'Wells Fargo' painted somewhere) in a desert landscape; small circular sign, atop a waist-high pole stand, nearby says BUS STOP; tall cactus etc. We could also show a 'bonobo' Indian Totem Pole 'Pyramid of Experts' somewhere, three bonobos tall, see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, just to add the recent philosophers' and experts' dimensions to the scene.

We see the coach relatively close up, from the side, so that we see inside windows on each side of the open stage coach door in the middle.

The coach is full of disparately dressed individuals.

He has already got one of them out of the coach and is standing next to the coach brandishing a six shooter at this unarmed individual, and has him by the scruff of the neck with the other hand. The Maverick has a Clint Eastwood type cigar stub in his mouth as he is talking.

This passenger might be a plump Arab, Mexican, Asian, or Indian-looking 'business man', 19th Century garb. He might also be Gandhi; Nehru jacket etc. He looks real scared. He is weighed down by two large, heavily stuffed, 'carpet bags', one in each hand.

A Marilyn Monroe figure, dressed in tight jeans and a tight white open blouse, as in The Misfits, is standing at the stop, holding a furled umbrella at arm's length pointed down smartly at an angle to her booted foot. Her blouse reads across the bosomy front, in block capitals 'I LOVE PHILOSOPHY'.

The caption above

Enforcing Human Rights and Free Trade 'In the Territories'

The caption below, he is saying

(

:

Think of 'Dusty''s voice from Tales of The Cowboys, Garrison Keillor.)

Mister, Stick 'Em Up! (Or: Stick Em Up Shorty!)

Don't give me that

'no direct investment' mambo jambo.

That jabber's for city slickers.

Gimme All Yur Free Trade, Now,

and Nobody'll Get Hurt: That's Yur Human Rites."

This re post dedicated to Barry Blitt. He doesn't do writing, just think of the images.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)